1. Understanding Income Statement

The income statement summarizes the sources of revenue and expenses for the company during the period. It is the step-by-step reconciliation of the firm’s books and records according to another fundamental accounting identity: Income = Revenues – Expenses The purpose of the income statement is to illustrate the conversion of the “top line” revenue, which represents the gross proceeds from the sale of the company’s products, into a “bottom line” net income to the common shareholders. This is done through a series of intermediate sums, each of which shows the impact of a different category of expenses.

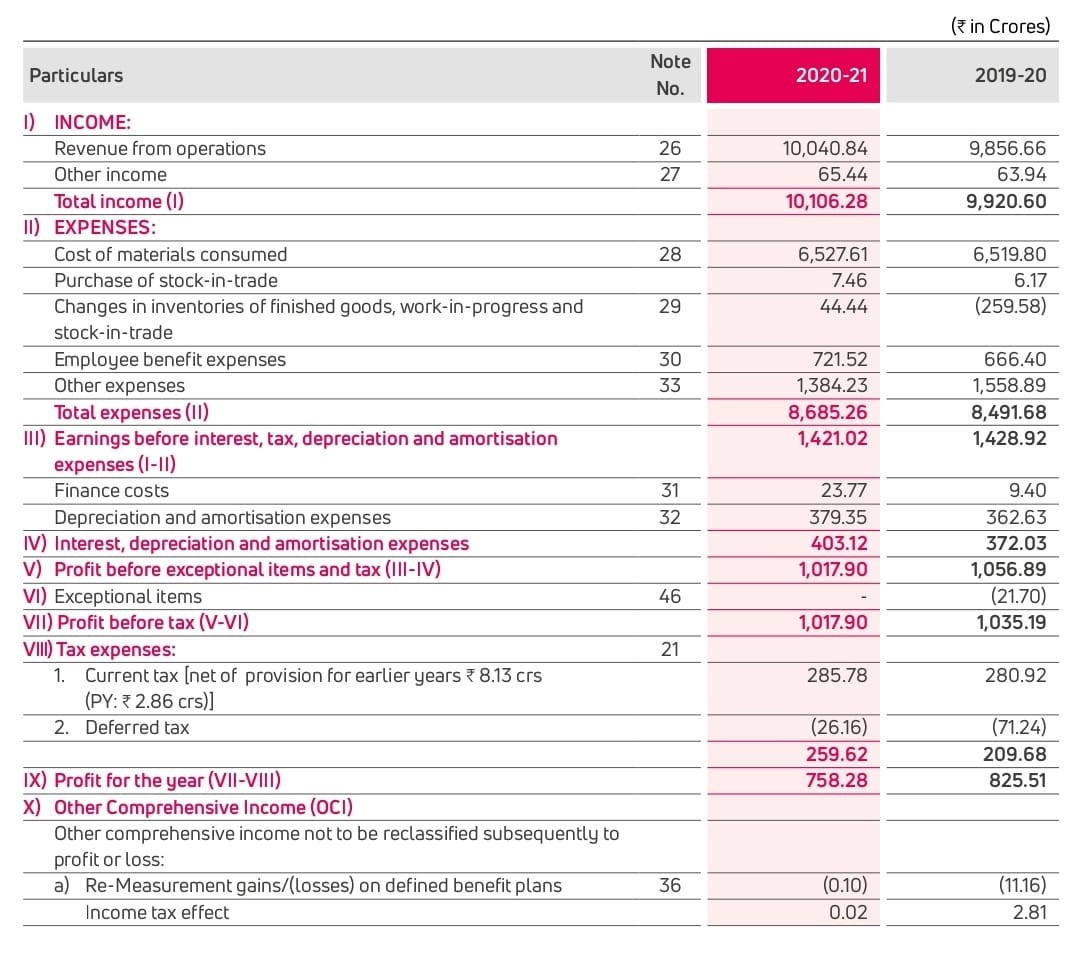

A sample income statement for Exide Industries is shown below:

2. Components Of Income Statement

Sales – Sales include the amount received or receivable from customers arising from the sales of goods and the provision of services by a company. A sale occurs when the ownership of goods and the consequent risk relating to these goods are passed to the customer in return for consideration, usually cash. In normal circumstances, the physical possession of the goods is also transferred at the same time. A sale does not occur when a company places goods at the shop of a dealer with the clear understanding that payment needs to be made only after the goods are sold failing which they may be returned. In such a case, the ownership and risks are not transferred to the dealer nor any consideration paid.

Companies do give trade discounts and other incentive discounts to customers to entice them to buy their products. Sales should be accounted for after deducting these discounts. However, cash discounts given for early payment are a finance expense and should be shown as an expense and not deducted from sales. Many companies deduct excise duty and other levies from sales. Others show this as an expense. It is preferable to deduct these from sales since the sales figures would then reflect the actual markup made by the company on its cost of production.

Other Income – Companies may also receive income from sources other than from the sale of their products or the provision of services. These are usually clubbed together under the heading, other income. The more common items that appear under this title are:

- Profit from the sale of assets – Profit from the sale of investments or assets.

- Dividends – Dividends earned from investments made by the company in the shares of other companies.

- Rent – Rent received from commercial buildings and apartments leased from the company.

- Interest – Interest received on deposits made and loans given to corporate and other bodies.

Cost of goods sold (COGS): These are costs that are directly attributable to the production of the goods sold, including both raw materials and labour. The calculation of the cost of the raw materials of production requires additional clarification. Most companies maintain an inventory of raw goods that are depleted and restocked according to the demands of production. In general, the items of inventory of a particular raw good are indifferentiable from each other (i.e., the screws, nuts, and bolts in inventory are identical to the new ones purchased) though the price the company pays for them may change over time (usually increasing). The difficulty comes in calculating the cost of the raw materials used in the production of the particular goods sold in the current period. If all the screws are identical, how do you know if you used the one that cost you $0.05 or $0.06? This problem of inventory accounting is solved by using one of three standard methods:

- Last in, first out (LIFO): As inventory is used in production, the assumption is that the most recently acquired inventory is consumed first. If the cost of the raw materials of production increases with time, this method will result in a higher cost of goods sold (and therefore lower profit).

- First in, first out (FIFO): The cost of the inventory consumed assumes the oldest inventory is used first. Increasing inventory prices will result in a lower cost of goods sold (and therefore higher profit).

- Average price: The cost of inventory is averaged between existing inventory and new purchases, resulting in a cost of goods sold that is usually somewhere between LIFO and FIFO. If there is a significant variation in material costs, there can be substantial differences in the valuation of the consumed inventory under the FIFO and LIFO methods. (These differences will also impact the balance sheet in the value of inventory.) To facilitate comparison between companies that use different inventory valuation methods, companies that use FIFO inventory valuation are required under GAAP to disclose a LIFO Reserve in a footnote on the balance sheet, which states the difference between the FIFO and LIFO valuations of inventory

Employee Costs – The costs of employment are accounted for under this head and would include wages, salaries, bonuses, gratuity, contributions made to provident and other funds, welfare expenses, and other employee-related expenditures.

Operating & Other Expenses – All other costs incurred in running a company are called operating and other expenses, and include.

- Selling expenses – The cost of advertising, sales commissions, sales promotion expenses and other sales-related expenses.

- Administration expenses – Rent of offices and factories, municipal taxes, stationery, telephone and telex costs, electricity charges, insurance, repairs, motor maintenance, and all other expenses incurred to run a company.

- Others – These include costs that are not strictly administration or selling expenses, such as donations made, losses on the sale of fixed assets or investments, miscellaneous expenditures and the like

Interest & Finance Charges – A company has to pay interest on money it borrows. This is normally shown separately as it is a cost distinct from the normal costs incurred in running a business and would vary from company to company. The normal borrowings that a company pays interest on are:

- Bank overdrafts

- Term loans taken for the purchase of machinery or construction of a factory

- Fixed deposits from the public

- Debentures

- Inter-corporate loans

Depreciation – Depreciation represents the wear and tear incurred by the fixed assets of a company, i.e. the reduction in the value of fixed assets on account of usage. This is also shown separately as the depreciation charge of similar companies in the same industry will differ, depending on the age of the fixed assets and the cost at which they have been bought.

Tax – Most companies are taxed on the profits that they make. It must be remembered however that taxes are payable on the taxable income or profit and this can differ from the accounting income or profit. Taxable income is what income is according to tax law, which is different to what accounting standards consider income to be. Some income and expenditure items are excluded for tax purposes (i.e. they are not assessable or not deductible) but are considered legitimate income or expenditure for accounting purposes

3. Measuring Profitability

The Basic measure of profitability than operating income is the gross profit, which is calculated simply as the difference between the revenue from net sales and the direct cost of producing the goods sold:

Gross profit = Net sales – Cost of goods sold

- Gross profit measures the revenue from the primary business of the company without factoring in any indirect costs. While it is impossible to run a company without incurring indirect costs, by comparing gross profit and operating profit between similar companies, it is possible to assess which company is running a “leaner” operation (though this is to some degree subject to each company’s classification of expenses as either direct or indirect).

- If the company has earned money from other sources not directly related to the operation of its business, this is added in as non-operating income. This allows for the distinction between how much the company earns from performing its core business (e.g., manufacturing and selling widgets) versus other sources of revenue that are not part of this core business (e.g., interest earned on credit extended to widget buyers). The sum of the operating income and non-operating income represents the total earnings of the company from all sources, less the costs of production (operating expenses). This is referred to as the earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) or pretax operating profit and is an important number because it isolates the revenues earned by the company from the impact of its choice of financing (the particular mixture of debt and equity used to fund its operations). This can be particularly interesting, for example, to an investor looking to potentially acquire the company since the financing and tax structure are likely to change after the purchase

- A common adjustment made to EBIT is to remove the accounting adjustments for depreciation and amortization, which do not represent real cash outlays in the period. This modified version is called EBITDA which, not surprisingly, stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA).

- The financing expenses, which represent costs associated with borrowed funds, are subtracted from the EBIT to get the pretax income. From this, we subtract the income taxes (either paid or provisioned for payment in the future) to arrive at the net income from continued operations (PAT). This measures the revenue generated by the firm from the pursuit of its business, after accounting for all costs (operational expenses, financing, and taxes).

- When corporations announce their quarterly earnings, one of the most closely watched components is the earnings per share (EPS), which is calculated as the net income to common equity holders, divided by the total shares of common stock outstanding. If 100 per cent of net income was paid out via dividends, the EPS would measure the percentage return to the shareholder on the purchase price of a share of stock (ignoring changes in the stock price). In practice, only a portion of earnings (if any) are paid out in dividends. The EPS then represents the return to the investor based on the combination of dividends paid out and his proportional claim on the retained earnings of the firm.

Summarising the Profitability Metrics

The income statement is used to assess the profitability of a company. Of the four most commonly used profitability measures, two start from the “top line” (Net sales) number and subtract out unwanted items, and two start from the “bottom line” (Net income) and add back in items that should not have been removed.

Top-Down

- Gross profit = Net sales – Cost of goods sold: This is the most basic measurement of profitability: It tells how much more than the cost of raw materials and production the company sell its products.

- Operating income = Net sales – Cost of goods sold – SG&A expenses: Anything described as “operating” refers to the core business of the company, excluding income from other sources. Operating profit is the gross profit (how much was made by selling the product) less the selling, general, and administrative expenses (what it costs to run the business).

Bottom-Up

- EBIT = Net income + Income taxes + Interest expense: EBIT (earnings before interest and taxes) adds back to net income the income taxes and interest expense to give a measure of how profitable the company’s business is, independent of the effects of how it is financed and how tax efficient it is. EBITDA = EBIT + Depreciation and amortization: Taking EBIT one step further, EBITDA adds back into EBIT the accounting adjustments for depreciation and amortization, which do not represent real cash outlays in the period.

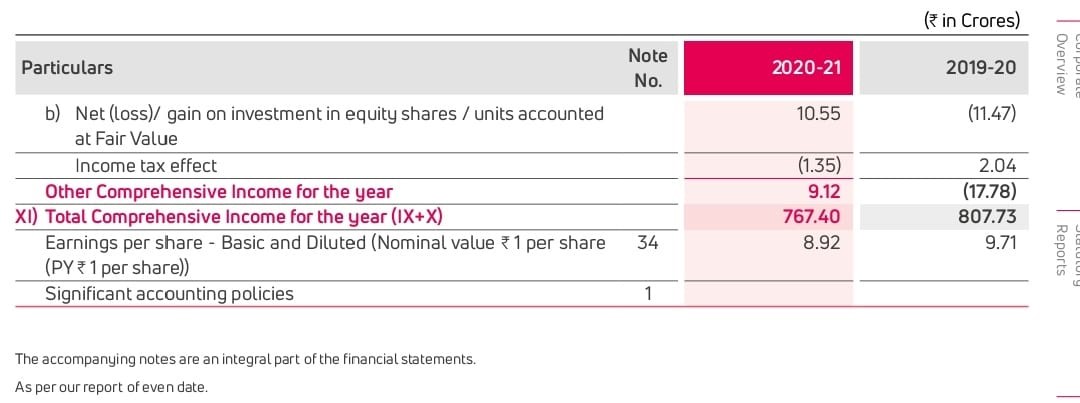

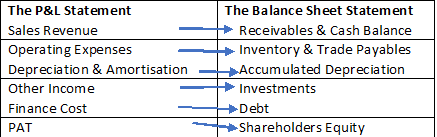

4. Connecting The P&L And Balance Sheet

Let us now focus on the Balance Sheet and the P&L statement and the multiple ways they are connected (or affect) each other:

Connecting the P&L & Balance Sheet

In the image above, on the left-hand side, we have the line items on a typical standard P&L statement. Corresponding to that on the right-hand side we have some of the standard Balance Sheet items.

To begin with, consider the Revenue from Sales. When a company makes a sale it incurs expenses. For example, if the company undertakes an advertisement campaign to spread awareness about its products, then naturally the company has to spend cash on the campaign. The money spent tends to decrease the cash balance. Also, if the company makes a sale on credit, the Receivables (Accounts Receivables) go higher. Operating expenses include the purchase of raw materials, finished goods and other similar expenses. When a company incurs these expenses, to manufacture goods two things happen. One, if the purchase is on credit (which invariably is) then the Trade payables (accounts payable) go higher. Two, the Inventory level also gets affected. Whether the inventory value is high or low, depends on how much time the company needs to sell its products. When companies purchase Tangible assets or invest in brand-building exercises (Intangible assets) the company spreads the purchase value of the asset over the economic useful life of the asset. This tends to increase the depreciation mentioned in the Balance sheet. Do remember the Balance sheet is prepared on a flow basis, hence the Depreciation in the balance sheet is accumulated year on year. Please note that depreciation in the Balance sheet is referred to as Accumulated depreciation.

Other income includes monies received in the form of interest income, sale of subsidiary companies, rental income etc. Hence, when companies undertake investment activities, the other incomes tend to be affected. As and when the company undertakes Debt (it could be short-term or long-term), the company spends money towards financing the debt. The money that goes towards financing the debt is called the Finance Cost/Borrowing Cost. Hence, when debt increases the finance cost also increases and vice versa.

Finally, as you may recall the Profit after tax (PAT) adds to the surplus of the company which is a part of the Shareholder’s equity.

Financial and Business expert having 30+ Years of vast experience in running successful businesses and managing finance.