1. Balance Sheet Meaning

The term balance sheet refers to a financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity at a specific point in time. Balance sheets provide the basis for computing rates of return for investors and evaluating a company’s capital structure. In short, the balance sheet is a financial statement that provides a snapshot of what a company owns and owes, as well as the amount invested by shareholders. Balance sheets can be used with other important financial statements to conduct fundamental analysis or calculate financial ratios.

Key Points

- A balance sheet is a financial statement that reports a company’s assets, liabilities, and shareholder equity.

- The balance sheet is one of the three core financial statements that are used to evaluate a business.

- It provides a snapshot of a company’s finances (what it owns and owes) as of the date of publication.

- The balance sheet adheres to an equation that equates assets with the sum of liabilities and shareholder equity.

- Fundamental analysts use balance sheets to calculate financial ratios.

2. Balance Sheet Fundamentals

The balance sheet is structured with assets on the left-hand side and liabilities and shareholders equity on the right. For an item to be considered an asset, it must have been acquired in the past and have the potential to generate a quantifiable economic benefit in the future. Liabilities are obligations acquired in the past that require economic sacrifices in the future. The difference between the assets and liabilities of the company is what is left over for the owners (shareholders) of the company. This is called shareholders equity. This leads us to one of the fundamental identities of accounting:

Assets = Liabilities + Shareholders equity

That is, the things a company has (assets) are either paid for with borrowed money (liabilities) or belong to the owners (shareholders equity). This identity means that the sum of the items on each side of the balance sheet must be the same – that’s why it’s called the “balance” sheet

For the two sides of the balance sheet to remain equal, the assets and liabilities of the company must be recorded using a process called double-entry bookkeeping. A single item cannot be added to the balance sheet in isolation – there must always be an equal and offsetting adjustment somewhere else to keep things balanced. This offsetting entry can be an equivalent addition to the other side of the balance sheet or a reduction in another item on the same side.

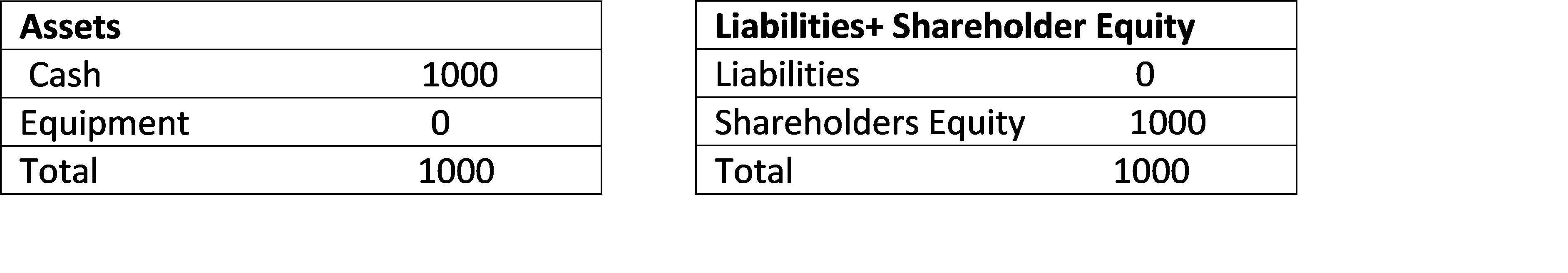

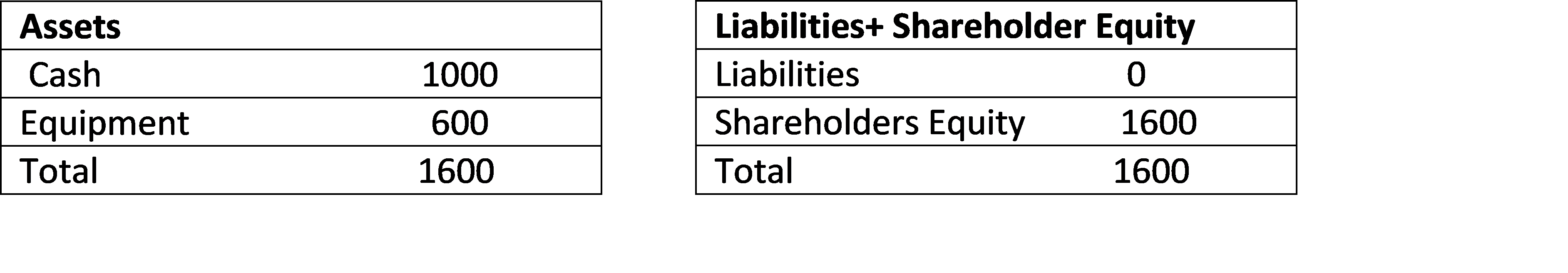

This is best illustrated by an example. Consider a brand new company that has yet to begin operation and whose only asset is Rs.1,000 of cash invested by the founders.

The company’s balance sheet looks quite simple:

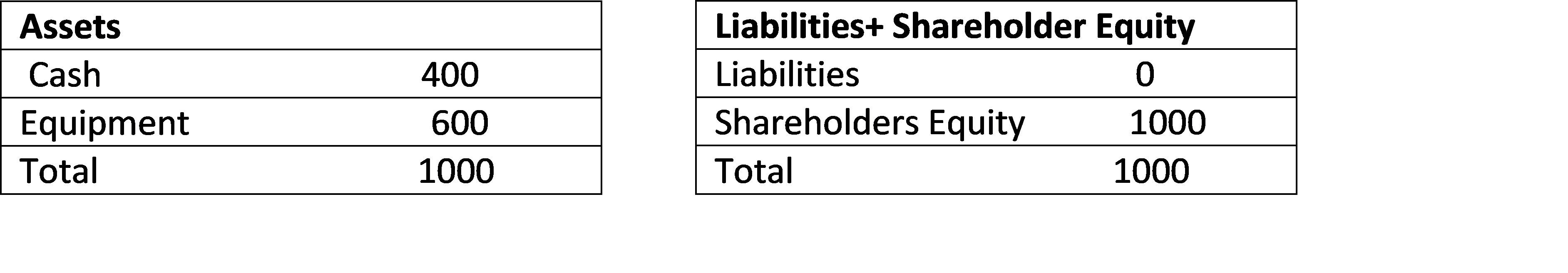

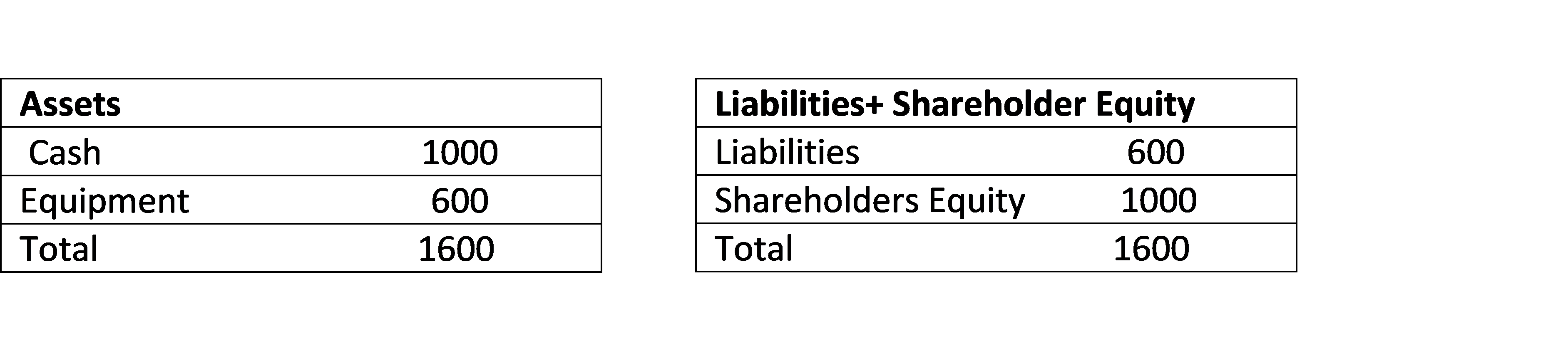

The company now purchases a piece of equipment for Rs.600. The management has three ways to pay for it: they can spend the cash they have, they can buy it on credit (get a loan), or the owners of the company can contribute more capital to pay for it. The three approaches are recognized differently on the balance sheet, but each one requires two entries:

Pay with cash: Two equal and offsetting adjustments are made to the left-hand side of the balance sheet. The Equipment line is increased by Rs.600 while the Cash line is reduced by an equivalent amount. The assets of the company have simply changed shape from cash to machines.

Pay with borrowed funds: If the machine is purchased with borrowed funds (credit), then the offsetting adjustment to the addition of Rs.600 to the equipment line on the left-hand side would be an increase in the liabilities of the company (the borrowed funds) on the right-hand side. This has the additional effect of increasing the total size of the balance sheet from Rs.1,000 on each side to Rs. 1,600. (The balance sheet is now leveraged by the addition of borrowed funds.)

Owners contribute more capital: The third option is that the owners of the company contribute additional capital to pay for the machine. In this case, the offsetting adjustment to the Rs.600 addition to the equipment line is an addition of Rs. 600 to the shareholder’s equity. The balance sheet increases in size from Rs.1,000 to Rs. 1,600 but there is no leverage.

In all cases, there are two entries to the balance sheet – one to record the change in assets, the other to record how it was paid for -or to whom it belongs (the owners of the company or the creditors).

Suppose, for example, that during installation the newly purchased machinery is damaged and its value is reduced from Rs.600 to Rs.400. The asset side of the balance sheet is now reduced by Rs.200 and there must be an equal and offsetting adjustment to the righthand side. If the machine was paid for on credit, the debt does not change just because the machine is worth less than before. The only place where the loss of Rs.200 on the asset side can be reflected is in the shareholder’s equity line. The owners of the company take the loss, not the creditors. In general, the shareholder’s equity line is calculated as a “plug”. That is, once all the assets and liabilities have been added up, the shareholder’s equity is defined to be whatever value makes the two sides of the balance sheet equal. Of the four items in this very simple balance sheet, three can be objectively measured: the cash holdings, the value of the equipment, and the amount of money the company owes. Shareholders’ equity is effectively defined as everything that is left over.

3. Balance Sheet Components

On both the asset and liability sides of the balance sheet, the contents are categorized as either current, consisting of liquid assets and short-term liabilities that will be used or paid off within one year, or long-term, which includes everything else.

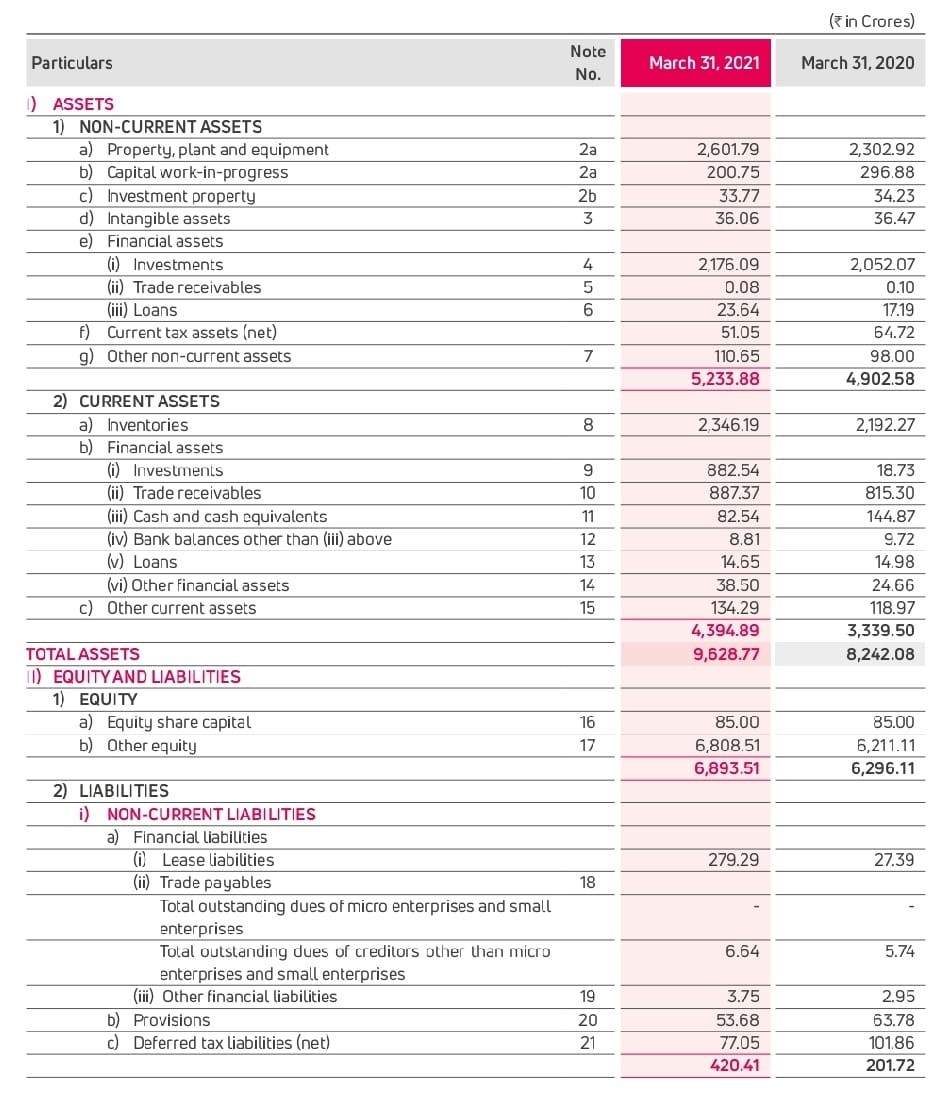

Example of a balance sheet of Exide industries

Beginning on the asset side of the balance sheet, important components are:

Current Assets – Current assets are assets owned by a company that are used in the normal course of business or are generated by the company in the course of business such as debtors finished stock or cash. The rule of thumb is that any asset that is turned into cash within twelve months is a current asset.

4. Current & Long Term Assets

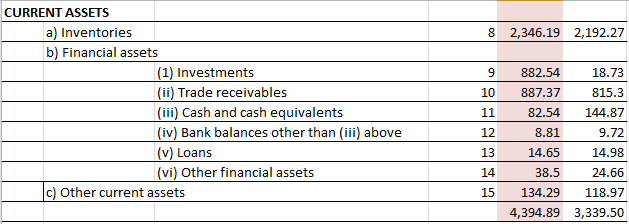

Snapshot of Current Assets of Exide Ltd: –

Current assets can be divided into:

1) Inventories – These are arguably the most important current assets that a company has as it is by the sale of its stocks that a company makes its profits. Stocks, in turn, consist of:

- Raw Materials – The primary purchase that is utilized to manufacture the products a company makes.

- Work In Progress – Goods that are in the process of manufacture but are yet to be completed.

- Finished Goods – The finished products manufactured by the company that are ready for sale.

2) Investments– Many companies purchase investments in the form of shares or debentures to earn income or to utilize cash surpluses profitably. When investments are done for less than one year period they are classified as current assets. Generally, investment in fixed deposits, short-term debentures and liquid mutual funds fall under the investment category

- Debtors/ Trade Receivables – Most companies do not sell their products for cash but on credit and purchasers are expected to pay for the goods they have bought within an agreed period – 30 days or 60 days. The period of credit would vary from customer to customer and from company to company and depends on the creditworthiness of the customer, market conditions and competition. Often customers may not pay within the agreed credit period. This may be due to laxity in credit administration or the inability of the customers to pay. Consequently, debts are classified as:

- Those over six months, and

- Others

These are further subdivided into;

- Debts considered good, and

- Debts considered bad and doubtful

If debts are likely to be bad, they must be provided for or written off. If this is not done, assets will be overstated to the extent of the bad debt. A write-off is made only when there is no hope of recovery. Otherwise, a provision is made. Provisions may be specific or they may be general. When amounts are provided on certain identified debts, the provision is termed specific whereas if a provision amounting to a certain percentage of all debts is made, the provision is termed general

- Prepaid Expenses – All payments are not made when due. Many payments, such as insurance premiums, rent and service costs, are made in advance for a period which may be 3 months, 6 months, or even a year. The portion of such expenses that relates to the next accounting period are shown as prepaid expenses in the Balance Sheet.

- Cash & Bank Balances – Cash in hand in petty cash boxes, safes and balances in bank accounts are shown under this heading in the Balance Sheet.

- Loans & Advances – These are loans that have been given to other corporations, individuals and employees and are repayable within a certain period. This also includes amounts paid in advance for the supply of goods, materials and services.

- Other Current Assets – Other current assets are all amounts due that are recoverable within the next twelve months. These include claims receivable, interest due on investments and the like.

Long-Term Assets:

Long-term assets (also called fixed or capital assets) are those a business can expect to use, replace and/or convert to cash beyond the normal operating cycle of at least 12 months. Often they are used for years. This distinguishes them from current assets, which companies typically expend within 12 months. Because they are harder to convert to cash than current assets, they are often referred to as non-current assets.

5. Non-Current Assets

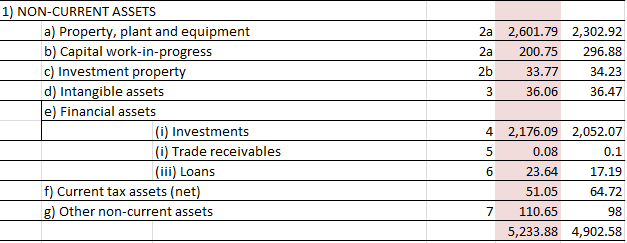

Snapshot of Non-current asset of Exide Industries

Non- Current Assets are divided into:

- Fixed Assets- These are assets that a company owns for use in its business and to produce goods. Typically it could be machinery. They are not for resale and comprise land, buildings i.e. offices, warehouses and factories, vehicles, machinery, furniture, equipment and the like. Every company has some fixed assets though the nature or kind of fixed assets vary from company to company. A manufacturing company’s major fixed assets would be its factory and machinery, whereas that of a shipping company would be its ships. Fixed assets are shown in the Balance Sheet at cost less the accumulated depreciation. Depreciation is based on the very sound concept that an asset has a useful life and that after years of toil, it wears down. Consequently, it attempts to measure that wear and tear and to reduce the value of the asset accordingly so that at the end of its useful life, the asset will have no value.

- Long-term investments: Assets owned by the company that are not directly related to the functioning of the business (e.g., a piece of unused land).

- Intangible assets: Money paid by the company for rights, patents, trademarks, and the like, which can produce value but do not have a physical presence.

The other side of the balance sheet is divided into two parts: current and long-term liabilities on the top, followed by the details of the shareholder’s equity.

6. Current Liabilities

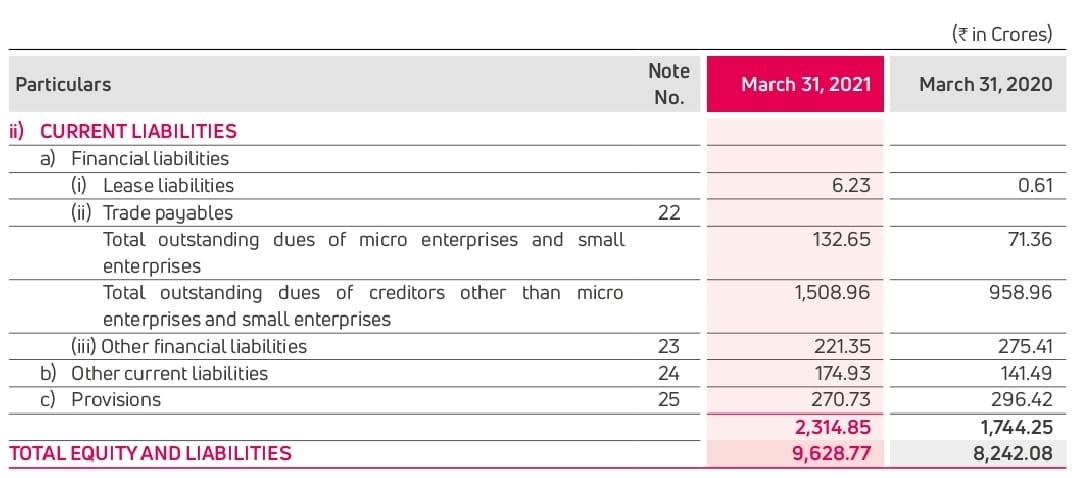

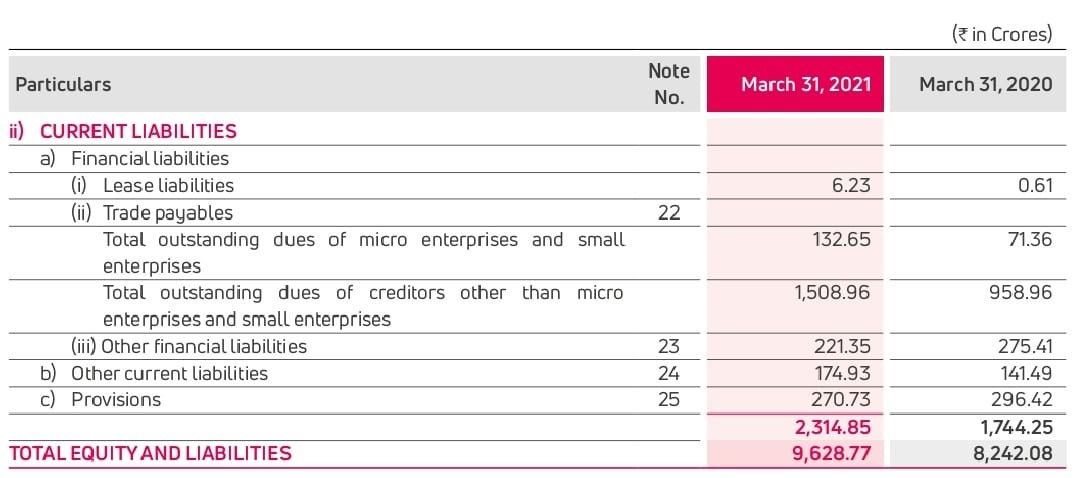

Snapshot of Current Liabilities of Exide Ltd: –

- Current Liabilities – Current liabilities are amounts due that are payable within the next twelve months. These also include provisions which are amounts set aside for an expense incurred for which the bill has not been received as yet or whose cost has not been fully estimated. They can be categorised as:

- Creditors – Trade creditors are those to whom the company owes money for raw materials and other articles used in the manufacture of its products. Companies usually purchase these on credit – the credit period depends on the demand for the item, the standing of the company and market practice.

- Accrued Expenses – Certain expenses such as interest on bank overdrafts, telephone costs, electricity and overtime are paid after they have been incurred. This is because they fluctuate and it is not possible to either prepay or accurately anticipate these expenses. However, the expense has been incurred. To recognize this the expense incurred is estimated based on past trends and known expenses incurred and accrued on the date of the Balance Sheet.

- Provisions – Provisions are amounts set aside from profits for an estimated expense or loss. Certain provisions such as depreciation and provisions for bad debts are deducted from the concerned asset itself. There are others, such as claims that may be payable, for which provisions are made. Other provisions normally seen on balance sheets are those for dividends and taxation.

- Other Current Liabilities – Any other amounts due are usually clubbed under the all-embracing title of other current liabilities. These include unclaimed dividends and dues payable to third parties.

7. Non-Current Liabilities

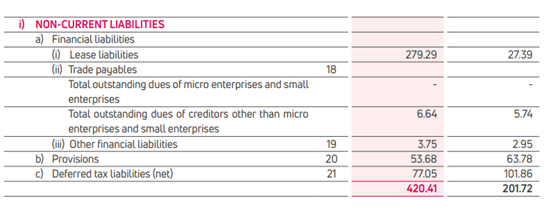

Snapshot of Non-Current Liabilities of Exide Industries: –

- Long-term debt: Any long-term debt obligation of the company. For a smaller firm, this is likely to consist mostly of bank loans while for a larger company, it can also include bonds and other debt obligations issued by the company itself.

- Deferred income tax liability: The method by which revenue and expenses are accounted for under GAAP is very different from what is required by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). As a result, companies will usually show a larger profit on their accounting statements (where it looks good) than on their income tax statements (where it means a higher tax bill). The difference between the two represents revenue that has not yet been taxed but will be at some point. The deferred tax liability indicates the pending IRS bill that will need to be paid when this happens.

Another liability that often appears on the balance sheet is something called minority interest. This entry appears on the balance sheet of a parent company that does not own 100 per cent of one of its subsidiaries. When a company acquires a sufficiently large portion of another company (usually more than 50 per cent), the full assets and liabilities of the acquired company are listed on the balance sheet of the acquiring (parent) company. An accounting adjustment is then necessary on the liabilities side since there is a portion of the subsidiary that is not owned by the parent.

As an example, assume that Company B has a book value of Rs.100 consisting of Rs100 in assets and no debt and that Company A can purchase an 85 per cent stake in Company B for Rs.85. Because it owns a controlling stake, Company A will now add all the assets of Company B to its balance sheet. The purchase price for 85 percent of the company is equal to 85 percent of the book value so there is no goodwill adjustment to be made. However, when the full assets and liabilities of Company B are taken onto Company A’s balance sheet, there will be a net increase of Rs15 in assets as the Rs100 of assets of Company B is added and the Rs.85 reduction in cash is recognized. The imbalance comes from the fact that 100 per cent of Company B has been added to the balance sheet but only 85 per cent has been purchased. Company A would then recognize a Rs.15 liability for minority interest to adjust for the 15 per cent of the company that is still owned by the previous owners.

8. Shareholder’s Equity

Snapshot of Non-Current Liabilities of Exide Industries: –

The last section of the balance sheet contains the decomposition of shareholders’ equity. Given the total assets and liabilities of the company, we already know what the total value of shareholders’ equity must be, simply by rearranging the fundamental accounting relationship stated at the start of the section:

Shareholders’ equity = Assets – Liabilities

In general terms, the shareholders’ equity can come from two sources: either the money was put into the company by the owners or the company earned the money from its business activities but has not yet paid it out to the owners. These two forms of shareholders’ equity appear on the balance sheet as follows:

- Paid-in capital: This represents the money paid by investors in return for fractional ownership of the benefits of the company, through ownership of common shares, either purchased in an initial public offering or a secondary share issuance. If a company issues 1 million shares of stock and sells them in an initial public offering (IPO) at Rs25 each, then the company will have Rs.25 million of common equity.

- Retained earnings: Profits earned by the company that have not been distributed to the shareholders via dividends are recognized on the balance sheet as retained earnings. This entry is not calculated in the preparation of the balance sheet but is the “plug” value whose value is determined by the difference between the assets, liabilities, and the other elements of shareholders’ equity whose value can be objectively determined.

Companies will sometimes repurchase their shares in the open market. When this occurs, the repurchased shares are represented on the balance sheet as treasury stock in the statement of shareholders’ equity. The value assigned is the repurchase price of the shares and carries a negative sign as they are effectively an offset to the paid-in capital (they were sold and then bought back). These shares no longer represent an actual obligation since they are held by the company itself and not by outside investors.

The sum of paid-in capital and retained earnings, less treasury stock, is the common shareholders’ equity. In addition to common stock, some firms will also issue shares of preferred stock. This is a special type of non-voting stock that has priority over common shares in the event of bankruptcy and liquidation of the company’s assets. Preferred shares usually carry a fixed dividend that must be paid before any dividends are paid out on the common stock. Preferred dividends are similar to interest payments on debt but with the important caveat that, should the firm be unable to pay the dividend, this does not force it into bankruptcy-the dividend obligation simply accumulates and must be paid out in the next period. While preferred stock is, in many ways, more like a bond, it is recognized as an equity issuance and therefore shows up under the shareholders’ equity rather than as part of long-term debt. The book value of preferred stocks is added to common shareholders’ equity to arrive at the total value of shareholders’ equity.

9. Capital

A firm’s capital consists of the financial resources at its disposal that can be applied to the production of the goods or services it offers. There are two common definitions of capital derived from the balance sheet. The first of these is working capital, which measures the short-term liquidity of the company and is equal to the difference between the current assets and current liabilities. A company must maintain an adequate buffer of working capital to guarantee that current assets are enough to cover short-term liabilities and avoid an interruption in operations due to an inability to make payments on its obligations. This underscores the significance of “current,” as it applies both to assets (they should be liquid and readily convertible into cash) and liabilities (anything that is coming due in the near term, including the current portion of long-term debt).

Working capital = Current assets – Current liabilities

A broader measurement of the resources a company has at its disposal is total capital, which is composed of all borrowed funds (short- and long-term) and cash supplied by the owners (shareholders’ equity). The only item from the right-hand side of the balance sheet that is not included is Minority Interest, which is an accounting entry and does not represent an actual source of funds.

Total capital = Current liabilities + Long-term debt + Shareholders’ equity

Financial and Business expert having 30+ Years of vast experience in running successful businesses and managing finance.